Is AI bad for the environment? While many studies point to high energy use across the AI industry, there is a big debate over just how significant the overall impact is. Supporters often highlight that all human activity has an environmental cost, and suggest that the cost-benefit ratio of using AI tools is higher than other day-to-day activities like watching Netflix.

For reference, watching Netflix consumes about 0.077 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity per hour, while the average ChatGPT query consumes about 0.00034 kWh of energy (we will review this claim in further detail below).

Taking a similar position, Andy Masley argues in a blog post that people using ChatGPT are often using less energy per minute than “almost” anyone else in the world. Masley suggests that printing a physical book consumes 5,000 watt-hours (Wh) of electricity, and that you’d be consuming more energy reading a book for 6 hours than you would be using OpenAI’s popular chatbot. (One kWh is equal to 1,000 Wh.)

On the other hand, critics point to the industry’s massive energy consumption. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that electricity demand from data centers will more than double by 2030 to roughly 945 terawatt-hours (TWh). This represents approximately 3% of global electricity demand, or more than the current consumption of Japan. (One TWh is equal to one billion kWh.)

Electricity Units Cheat Sheet:

- Watt-hour (Wh) → An 8-watt LED light bulb (a typical household bulb) used for one hour consumes 8 Wh of energy

- Kilowatt-hour (kWh) → one thousand watt-hours

- The average American home uses 30 kWh per day

- Megawatt (MW) → one thousand kilowatts

- Atlanta’s airport uses 30–50 megawatts. The biggest datacenters are comparable in power consumption to a major airport.

- Gigawatt (GW) → one million kilowatts

- A bolt of lightning produces 10 GW but only lasts for a millisecond

- Terawatt (TW) → one billion kilowatts

We’ve also seen tech giants like Google and Microsoft significantly increase their energy demand thanks to investments in data centers amid the AI race. So while it’s true that household goods and activities consume lots of electricity in their own right, this level of electricity consumption across the industry does warrant scrutiny.

At the moment, key players in the industry like OpenAI and Anthropic don’t offer comprehensive data detailing electricity usage and carbon emissions. This makes it difficult to hold them accountable for irresponsible or wasteful practices.

Discussing the electricity consumption of modern models, and potentially even putting pressure on regulators to mandate disclosure, could prove vital in encouraging AI vendors to fully embrace sustainable development practices.

The environmental cost of AI

One of the most common claims shared during the craze was that ChatGPT consumes a bottle of water per prompt. While this is somewhat hyperbolic, study after study indicates a measurable impact on the environment, including carbon emissions, water evaporation, and even climate change.

A blog post released by Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, provides his estimation of electricity consumption, suggesting that the average ChatGPT query uses about 0.34 watt-hours of energy.

This is equivalent to turning on a high-efficiency light bulb for a couple of minutes and consuming just 0.000085 gallons of water, the equivalent of one-fifteenth of a teaspoon—a far cry from the claimed “bottle of water” per prompt. However, Altman’s calculations should be taken with a healthy dose of skepticism, given his vested interest in promoting OpenAI; third-party estimates offer a more alarming picture.

Researchers are raising red flags

The carbon accounting provider Greenly finds that training and using GPT-4 to respond to 1 million emails per month could generate 7,138 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent gases (tCO₂e) per year. That’s the equivalent of 4,300 round-trip flights between Paris and New York.

Though the issue of water evaporation is still not quite equivalent to a “bottle of water” per prompt (assuming a standard 20 oz bottle), for some older AI models, it may be much higher than Altman’s claim. UC Riverside researchers suggest that GPT-3 (an older model no longer in wide public use) consumes 500ml of water for every 10–50 medium-length responses, depending on where it’s deployed – that’s just shy of 17 oz, and was at least part of the inspiration for the bottled water claim.

The impact of water evaporation also rises significantly if we consider training the LLM itself, with the Riverside study finding that training GPT-3 in Microsoft’s U.S. data centers can directly evaporate 700,000 liters of clean freshwater. By 2027, the study estimates that global AI demand could consume more than the total annual withdrawal of Denmark, amid a freshwater scarcity crisis.

This research is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to measuring AI’s impact on the environment. It’s also likely that this level of consumption will grow as models become increasingly complex with a greater number of parameters.

Experts say the long-term impact is uncertain

Now that GPT-5 has launched, consumption is likely to increase further. Less than a month after the model’s release, researchers at the University of Rhode Island’s AI lab estimate that producing a medium-length 1,000 token response with GPT-5 could consume up to 40 Wh of electricity, at an average of 18.35 Wh, a significant increase from GPT-4’s average consumption of 2.12 Wh.

That said, Alexis Normand, CEO and co-founder of Greenly, notes it’s very challenging to assess how the long-term demand for electricity will change as AI advances.

“It’s hard to say what the final impact of AI would be, but in the short term, it’s a massive increase in electricity demand, which has [an] impact on data centers’ carbon footprint. In the midterm, it might be that this extra electricity demand will translate into extra demand for renewable energy or for nuclear energy—which might end up being good for the energy transition, but we don’t know,” Normand said.

“[Energy consumption was] growing 10% per year before AI, and now it’s more like 30%. So it’s crazy,” Normand said. “There might be some good that comes out of it, but it creates a big strain on our electricity grid space.”

Why are AI models so power-intensive?

To measure the true energy cost of AI, we must consider the long-winded process of training the model up front as well as the ongoing energy used when entering prompts. Factors such as the energy used to harvest the raw materials for infrastructure like semiconductors and GPUs, along with the wider manufacturing process, should also be considered.

In most evaluations, the data center is the central point of focus since this is the facility where model training takes place. Electricity consumption in the data center is quite high, with a single hyperscale data center drawing between 20 and 100 megawatts. For comparison, an international airport like Atlanta consumes 30–50 megawatts.

The level of energy consumption will depend on the type of energy the facility relies on (fossil fuels, nuclear power, wind power, or solar) and its associated infrastructure. In general, energy consumption at data centers is high due to the amount of high-performance hardware required for an AI model to function.

Top-performing models like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok require a large data center of AI servers with powerful GPUS to function. For example, OpenAI plans to build a data center in Norway with 100,000 Nvidia GPUs by 2026.

The larger the model, the more resources required

As a general rule of thumb, newer models like GPT-5 or 4o consume more electricity than older models like GPT-4 or GPT-3. Looking back at GPT-3, a study released by Google and the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that the model’s training process consumed 1,287 megawatt-hours of electricity. That’s equivalent to powering 120 average U.S. homes for a year and generating 552 tons of carbon dioxide.

This consumption can increase significantly for more complex models, with one estimate suggesting that a single short query with GPT-4o consumes 0.42 Wh per prompt–—scaled to 700 million queries a day, that’s electricity use on par with 35,000 U.S. homes and carbon emissions that would require a forest the size of Chicago to offset.

Not only does running a data center consume electricity and generate carbon emissions, but it can also consume vast volumes of water (used to cool the infrastructure and prevent overheating). That being said, it’s worth noting that some data centers may use alternative cooling mechanisms, such as closed-loop, air-cooled, or hybrid systems that reduce or eliminate water consumption.

Are AI companies doing enough to control carbon emissions?

One of the most pressing issues around the energy consumption of AI is whether or not industry leaders like OpenAI and Anthropic are doing enough to control it.

As of August 2025, while major cloud providers like Microsoft, Google, and AWS are powering their data centers with carbon-free energy or have plans to do so by 2030, top startups like OpenAI and Anthropic still haven’t disclosed how much energy products like ChatGPT and Claude 3 take to train.

Lack of disclosure around energy consumption makes it difficult for consumers to make informed choices about what tools they use. In an interview with Innovating With AI, Normand shared details about a brief encounter with Sam Altman, which raised concerns about the company’s commitment to sustainability.

“I actually met Sam Altman two years ago… Because of my role as CEO of Greenly, I had to ask what the carbon footprint of AI was. And he said something like, ‘Look, this is a great question, but… not a lot.’ I… realised he wasn’t very sincere or interested in the whole matter.”

Normand also shared that Greenly’s research team found Altman’s claims about the average ChatGPT query using 0.34 watt-hours of energy to be “dubious claims,” and suggested it could be at least 10 times higher.

Normand said he didn’t believe that Altman was being intentionally misleading; rather, perhaps he was unaware of the nuances of the topic. But he did conclude that many in the industry lack the level of professionalism on these topics that they require. In any case, it’s indicative that the industry as a whole needs to be much more proactive and transparent about offering consumers detailed information about the real-world impact of these models.

But it is important to note that the industry, as it stands, does not offer much transparency into its energy consumption. For instance, providers like OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, Google, and Microsoft do not, and are under no legal obligation to, share their energy emissions. This makes it difficult to ensure responsible use and development of these technologies.

Demands for eco-friendly AI are on the rise

AI’s environmental impact may be significant, but some key innovations in the industry illustrate a greener approach to long-term development. For example, providers like Amazon have started using renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, to support their data centers.

Likewise, although Anthropic hasn’t disclosed its carbon emissions, the startup does claim to work with “cloud providers that prioritize renewable energy and carbon neutrality,” with the goal of maintaining a “net zero climate impact on an annual basis.” However, without more detailed figures, it’s difficult to assess the scale of these green initiatives accurately.

Jeff Le is the former deputy cabinet secretary to former Governor of California Jerry Brown, who helped lead cyber event and incident response in Silicon Valley from 2015 to 2019. He believes there is a growing demand for transparency regarding these model emissions within the industry.

“I think there are community members really trying to push on this, like active transparency that searches what you use and tells you specifically what the number is for CO₂, or on water consumption, or whatever the metric you want to use, like electric [usage], whatever that might be,” Le said. “I think the average consumer would be very curious about that.”

Smaller LLMs and other moves towards energy efficiency

Although the industry has a long way to go toward offering consumers eco-friendly solutions, we are seeing a number of smaller language models with fewer parameters, like Phi, stepping up to provide a high-performance and energy-efficient alternative to more complex LLMs.

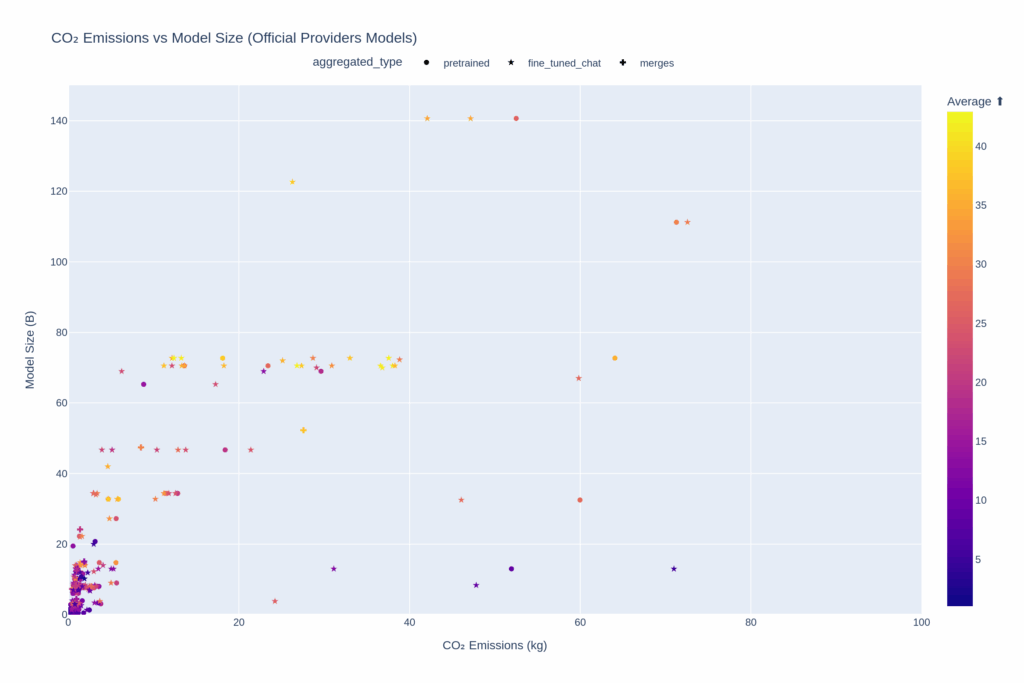

At the start of 2025, HuggingFace, an open-source AI model hosting platform founded by French entrepreneurs Clément Delangue, Julien Chaumond, and Thomas Wolf, valued at $4.5 billion, shared a breakdown of its Open LLM leaderboard. It showed that smaller models like Qwn-2.5-14b and Phi-3-Medium offer users the best leaderboard score-to-emission ratio.

These language models generally range between 1 million and 10 billion parameters, and require less overall compute resources than larger models. They’re also capable of running on-device on smaller devices like cellphones and consumer laptops, which makes them extremely power-efficient.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that AI chips designed for on-device processing could offer a 100–1,000-fold reduction in energy consumption per AI task compared to cloud-based AI. Processing could happen locally rather than transmitting data back and forth between a data center and an edge device, as is the case with AI systems that rely on cloud processing.

Ways AI can reduce energy consumption and carbon footprint

On the back end of the industry, AI also has a role to play in helping solutions providers to optimize their operations. For instance, companies in sectors like oil, gas, and manufacturing can use AI to unlock insights that can reduce overall power consumption.

A study from the IEA suggests that widespread adoption of AI in light industry, such as manufacturing, electronics, or machinery, could lead to energy savings of 8% by 2035. The report also notes that AI use in transportation could enhance vehicle operation and management, and reduce energy consumption.

Other research from the IEA indicates that the widespread adoption of AI applications could lead to 1,400 Mt of Co₂ reductions in 2035. While there is still much more research that needs to be done into the potential energy savings possible with using AI vs its overall consumption, there does appear to be some potential positive impacts.

It’s also worth noting that we’re starting to see vendors adopt more energy-efficient training methods, utilizing techniques like retrieval augmented generation (RAG) that have the potential to increase accuracy while also reducing electricity usage by up to 172%.

Why AI providers should disclose energy use

Although there are environmentally-conscious approaches to AI development emerging, these efforts are overshadowed by the fact that the biggest players in the industry don’t offer full transparency over the consumption of their models. This makes it very difficult for consumers to make informed decisions on what tools they want to use and how they use them.

“I think we can agree these tools have the potential to do incredible things. It’s just that you and I may be using these tools to make superhero caricatures of you and me, which is really fun, but I think there’s a legitimate question about whether that is a good use of these tools… versus using this for thought, scholarship, or leadership?” Le told IWAI.

“If a consumer were given a choice [such as] levels of energy usage to get an answer, I think people would consider that pretty seriously.” Le suggests there “could be a consumer movement toward energy-efficient solutions.”

For the AI industry to thrive, it needs to be built in a sustainable way. Giving consumers, businesses, journalists, and regulators access to the raw data would go a long way toward holding vendors accountable for irresponsible practices and wastage, while shining a light on those who are pioneering energy-efficient approaches.

Without external scrutiny, there will be no external pressure on these companies to reduce emissions. Today, there is little incentive for for-profit companies to disclose energy usage, as the PR fallout could alienate potential customers and investors. It may be time for regulators to step in.