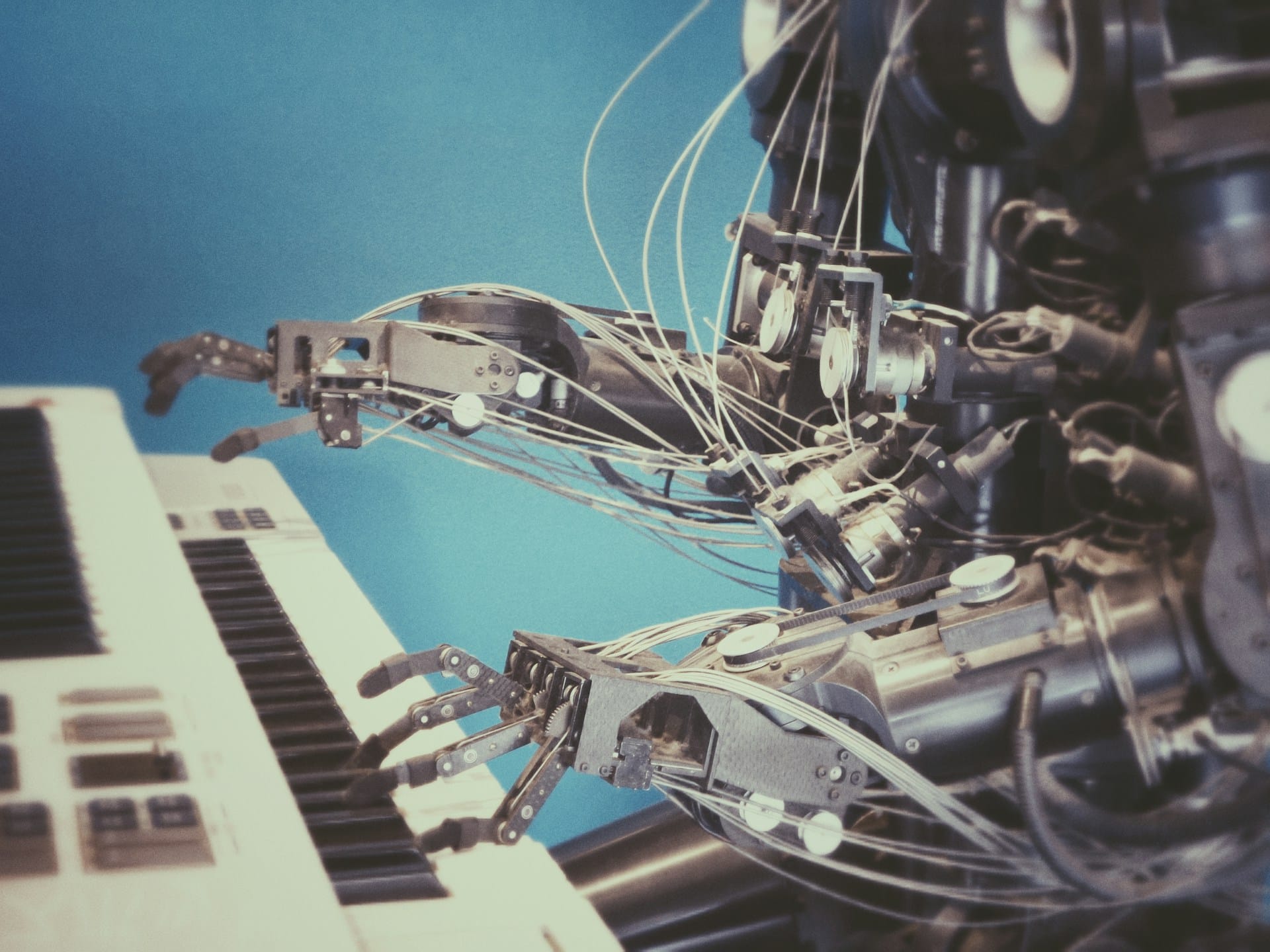

Generative AI has been one of the most talked-about technologies of the 2020s, and one of the most controversial use cases for this technology has been in creative endeavors. From using DALL-E or Midjourney to spit out Internet memes to some websites publishing articles entirely generated by ChatGPT, both audiences and creators are having a hard time avoiding the resulting content.

To get a better idea of how this technology is affecting art and the making of it, as well as potential use cases for AI, we surveyed artists from a variety of different mediums, including music, visual arts, and literature, to get a better understanding of how they’re feeling about the impact AI has had on their medium and associated industry.

How does AI in art work?

Artificial intelligence doesn’t refer to one specific technology as much as it’s a stand-in term for a variety of different tools and models. However, the basic way AI models function is through taking in data, analyzing it, and using patterns generated during analysis to output results. Intelligent chatbots for a popular software may be given the product’s user manual as their primary dataset, and use it to answer consumer questions. Or, DeepAI’s Music Generator can be fed a musician’s entire discography and output a song in that musician’s style. The possibilities are extensive.

Arguably, the most controversial aspect of using AI in art is the use of existing content to train AI models like ChatGPT and DALL-E, which leverage large, publicly available datasets to train their models at scale. This inevitably means artists’ creative work is being used to train these models—without their consent.

On top of the obvious copyright concerns, this can make AI-generated work appear, to some, as inherently plagiaristic. This might go a long way in explaining why respondents to our survey near-universally expressed little to no interest in their own art being used to train AI models. This was true even for respondents who were more positive about AI in their other answers.

When asked if their opinions on a piece of art changed after learning it was AI-generated, the overwhelming majority of respondents stated their view of the art changed for the negative, with only 9% of respondents stating their view of the art did not change. No respondent said their view of the artwork changed positively when learning it was AI-generated.

AI is a generator, not a creator

The majority of survey respondents also expressed little desire to utilize AI in the making of their own art, with only one respondent reporting that they actively used AI directly in the making of their art, perhaps by using DALL-E for image generation or ChatGPT to iterate a short story.

This result shouldn’t be surprising. For many artists, much of the joy of creating art comes from the process of creation itself; from actually making the art from scratch with their hands and minds. Discovery is a crucial aspect of that process. Whether it’s reading books to find new ideas for a story or finding riffs or melodies in music to alter and use in your own songs, there can be a palpable excitement in finding new ways to approach artistic expression.

AI can help with this discovery process, as many search engines have integrated either in-house AI models (Google Search’s AI Mode) or third-party models (DuckDuckGo’s duck.ai which can be used to talk to ChatGPT and Anthropic’s Claude, among others). This can help users find new or interesting sources on the Internet from which to draw inspiration.

AI is far from perfect

The effect AI has on the discovery process and other aspects of the creative process might not be entirely positive. Innovating With AI spoke with Atte Oksanen, a Professor of Social Psychology at Finland’s Tampere University, who has co-authored several research papers on the use of AI in art. He shared some of his thoughts on the subject:

“If you rely too much on AI, for example, you kind of lose the fascination of the total process. I talked [in one of] my other projects, and we interviewed people from different fields in the work life, and some of them were software developers, and they kind of said that nowadays they are using so much AI that they lose the fascination of doing the kind of normal routine coding that they used to learn earlier on. Of course, there’s a lot of routines and a lot of kind of repetitive tasks, but some people also mentioned that you kind of lose some of the fascination as well, because then you are just prompting and letting AI do [the work].”

The widespread use of AI in art is, of course, still very new, and it’s difficult to say right now if AI will help or harm new artists’ love for the creative process. There are even concerns by some that the technology may harm career prospects, as non-artists are increasingly using these tools to handle quick projects that they would have previously hired human artists for.

The utilization of AI to generate creative works has also been negative in other ways. One example is the impact on how people view certain types of art or certain patterns found in art. In journalistic writing, for example, AI checkers will sometimes mark articles written entirely by human hand as AI-generated due to the writer’s use of the em dash—a common punctuation mark in professional writing.

Another example can be found in a 2021 article by University of Colorado Boulder professor Harsha Gangadharbatla, who found that “Individuals… are likely to associate representational art to humans and abstract art to machines.” This can lead to artists working in visual abstract art being decried for using AI despite a total lack of the technology being used in the process.

AI as a tool in the creative process

While the majority of our respondents were not open to using AI to generate their art, 13% stated that they did use AI in other parts of the creative process. This seems to be the prevailing opinion amongst creatives who do utilize AI in the creative process: they use AI as tools to help with certain parts of creating their art but not as the medium through which their art is created.

In an interview for this article, Oksanen said:

“I think for writing, it could be used as a background tool, but it’s a matter of no matter what type of writing…it’s really a matter of [the artist] to decide how much he wants to use the AI…”

One of our survey respondents, author and editor Brette Sember, expressed similar sentiments. “[AI] is a great tool to assist you with various research and development items, but it should not be a replacement for your work as a writer.”

Both Professor Oksanen and Sember are speaking on writing, as that is their primary creative medium, but this sentiment can be extended to other mediums. Oksanen explains that, for example, musicians might use AI for parts of the process but that musicians would “still compose the music.”

A musical example that predates the current AI boom is Yamaha Corporation’s Vocaloid software. Most famous as the medium through which the world was introduced to popular mascot Hatsune Miku, Vocaloid’s singing voice synthesizer software has been publicly available since 2004. While the original software was just a voice synthesizer with no AI, the current Vocaloid product, VOCALOID6 proudly touts its use of AI to, “generate a highly expressive singing voice that’s more natural than ever before.”

Final thoughts

If there is a future for AI’s continued use in art, it’s likely in a support role—as a tool to enhance the creative process and not as the primary means by which the art is made. Generative models are supposedly improving over time as their datasets get more and more refined, but they will never fully—or even mostly—replace artists.

Competitive esports like Street Fighter 6 or League of Legends or even a traditional competitive game like chess offer some insight into why this might be the case. It’s very easy to create machines that can out-perform humans in these respects; IBM chess computer Deep Blue defeated chess grandmaster Gary Kasparov in 1996, and chess computers have only gotten more adept at the game since.

However, chess computers are nowadays relegated to their own competitive league, while grandmasters like Kasparov or Magnus Carlsen are still held up as the best the game has to offer. This is because, despite chess being a realm where AI has more or less completely outpaced humanity, watching humans puzzle out their options over the chessboard is still preferable to watching computers make invisible calculations.

The same could be true of the arts. No matter how accurately ChatGPT can generate works in the style of Shakespeare, Hemmingway, or Haruki Murakami, no matter how skilled DALL-E becomes at generating representational art, there will still be an undeniable desire for art made by human hands, with human minds. Theatre survived the advent of film, film survived the advent of television, and television survived the advent of online video. So, too, will human creativity survive the rise of AI-generated art.